by Batsheva C. Fryer-Cat (2002-2018), as dictated to her person (2013)

What is it like to be a sabbatical cat?

It’s very pleasant as long as you manage your expectations. In fact, it’s not so different from being a regular cat.

True confession: When my person informed me that we were going to take a six-month sabbatical, I bit her. I’m not sure why I reacted this way. I think I was anxious because my person was buried in a cloud of paper and kept staying at work late to “tie up loose ends” and hadn’t been spending a lot of time with her cat. As the cat, I wasn’t quite sure what “sabbatical” meant, but I thought that adding a new activity to the current roster was a recipe for disaster.

After I got over being upset, and once my person explained what “sabbatical” meant, I felt much better. Indeed, I was excited. I had many expectations that turned out to be wrong. For example, I thought that when my person was on sabbatical, she would be at home all day, or at least come home for lunch every day, or at least serve my favorite meal, tuna fish on a bed of raw spinach, garnished with potato chips, every time she did come home for lunch. None of this actually happened. In fact, all of this failed to happen within the first 48 hours of our sabbatical. I had to lower my whiskers and adjust my expectations. A sabbatical cat is basically just a regular cat whose person is leading a slightly more reasonable life and paying a little more attention to the cat. Once I realized this, I settled down to a very satisfying sabbatical.

How can I support my person who is on sabbatical?

Sabbatical people live more like cats than regular people do. Regular people are more like dogs: they spend a lot of time rushing around and barking at things and trying to look important. They worry a lot about who’s the alpha dog and who’s the beta dog and who’s the treed squirrel. Sabbatical people, like cats, have things they need to do, and things they need to think about, but they proceed at a deliberate, dignified pace. They practice feline self-direction rather than engaging in canine status games. If they want to spend an entire afternoon on a single focused project—like, say, trying to find out what’s behind the row of books on the bookshelf—then they do so. They don’t apologize for this. They don’t ask anyone’s permission. They just pursue their intellectual curiosity to its natural conclusion. If all the books fall off the bookshelf, then oh well. It is right and proper to make a mess in pursuit of knowledge.

You can help your person be a good sabbatical person by modeling a proper feline mode of engagement with the world. Lighten up on the morning routine; you don’t need to get your person out of bed at daybreak anymore. You should still enforce bedtime, however. Sometimes the person may be seized with inspiration (“I want to change all of the assigned reading for the course I’m teaching next year! Let’s rewrite the syllabus right now!”) at an inconvenient hour like 10 p.m. If this happens, I recommend: (1) scowling; (2) pouncing; (3) chewing; (4) unplugging the computer; (5) unplugging the lamp; (6) stomping out and modeling a proper feline approach to bedtime in another room.

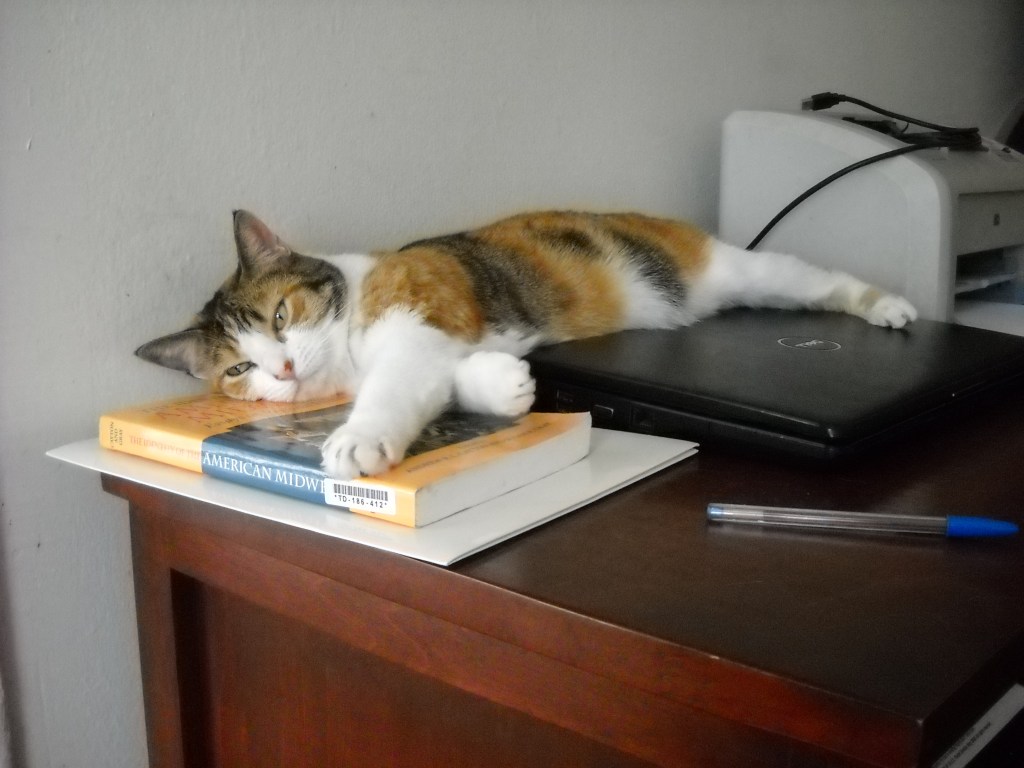

The person may need some tough love while he or she is easing into sabbatical mode. If you think your person is going out too much, sit on the briefcase until the person gets the message. If need be, sit on the person directly. The person may concoct excuses to remove you. (“The tea kettle is whistling, and it will set off the smoke alarm if I don’t turn the burner off right now.”) Pay no heed. Your sabbatical person needs to learn to sit down and focus on a project—or a cat—for an extended period of time without being distracted by distractions.

What should a cat do on sabbatical?

Don’t plan to nap all the time. That’s not what sabbaticals are for. It’s important for a sabbatical cat to have a project or two to keep her busy when she’s not asleep and her person is otherwise occupied.

I have undertaken two projects. One, figuring out what’s really going on in the hallway of my apartment building, is a long-term project that I have been engaged in for several years. Sabbatical is a good time to work on it because my person is home more so I have more opportunities to go out and sit in the hallway for fifteen or twenty or even thirty minutes at a stretch. I get to observe the hallway at different times of day and on different days of the week. I have made expeditions to the fourth and fifth floors. I have secured social invitations from neighbors my person doesn’t know. I have not yet come to any firm conclusions, but I am enjoying the research process, which is what I think sabbaticals are all about. Cats are very good at enjoying the research process. This is another feline attitude you should endeavor to model for your person.

My other sabbatical project involves hiding behind different pieces of furniture in artistic poses. I undertook this project because I thought it would be fun. Also, it’s something that can be done in my own apartment, when my person is not available or refuses to open the door to the hallway. While my hallway research project capitalizes on my analytical skills, my hiding behind the furniture project uses the creative side of my brain. I look on it as a type of performance art. I am a middle-aged cat now, and I don’t run and jump as well as I used to, but I find creative satisfaction in using all of the found spaces in my apartment.

Do sabbatical cats get more sleep than other cats?

This is a complicated question. I would say that sabbatical people get more sleep than other people, but sabbatical cats have some tough decisions to make.

Living with a sabbatical person can disrupt a cat’s routine. If you are accustomed to taking an 8 a.m. nap, you may find there is now a person around at that hour. Stuff could be happening: beds being made, newspapers unfurled, litter boxes cleaned. It is possible that food will be prepared at this hour. You will have to decide whether to involve yourself in these activities or stick to your routine and let the person clean the litter box unsupervised. Do you want to hear the refrigerator being opened and not run to see what’s going to come out of it? Furthermore, people come home earlier when they don’t have an endless string of late afternoon faculty meetings to attend. Sometimes they even come home for lunch. It can be difficult to find a window of opportunity for a four or five-hour nap.

What to do? One option is to pretend you’re a person and adopt a human schedule, which entails getting a lot of sleep at night and practically none during the day. The other option is to remember you’re a cat, arrange yourself on the best armchair, and sleep like a four-week-old kitten no matter what is going on around you. Either approach can work well. Personally, I would seize the special opportunities that a sabbatical poses by the ears and catch up on sleep when your person goes missing (see below).

Am I going to have difficulty keeping track of my person on sabbatical?

Very likely, yes. The word “sabbatical” is etymologically related to a Hebrew root meaning “cessation” and to the Biblical concept of the sabbatical year. This may sound promising, but unfortunately, many people think “sabbatical” is synonymous with foreign travel. Sabbatical people can be very difficult to keep track of! They come in two main varieties: the people who totally disappear for months on end, and the people who just make short trips because they think this is less traumatic for the cat, though in fact the cat gets her whiskers wound up anyway because she never knows whether her person is coming or going.

Be realistic in your approach to managing human travel. Once the suitcase is packed, it will be almost impossible to change the person’s mind. Before the suitcase is packed, it is presumably more possible to influence the person’s plans, but this is not helpful because it is difficult to divine what the person is thinking before the suitcase comes out. The span of time between the moment when the person reveals her plans and the moment when the suitcase is packed is heartbreakingly brief.

For these reasons, I recommend adopting a fatalistic attitude. In most cases, you will see more of your person as a sabbatical cat than you do as a regular cat despite sabbatical people’s propensity to travel. You just have to tolerate the human yen for travel as the price you pay for being a sabbatical cat, and trust that there will be ear-scratching time when the sabbatical person returns. At least you’re not the one getting on an airplane.

In some extreme instances, sabbatical cats are obliged not only to tolerate the sabbatical people’s absence but also to travel themselves. Some cats I know were sent to South Carolina for three months while their people went to Europe. All I can suggest to cats who find themselves in this predicament is to devise a project that meshes with the plans your people have made for you. A sojourn in South Carolina could present some interesting opportunities if your sabbatical project is to improve your lizard-hunting skills. On the other hand, if you spend three months hiding under the sofa, you may find it less fulfilling.

When (don’t kid yourself with “if”) your sabbatical person goes missing, you will almost certainly have a substitute person to manage. No matter how wretched you feel, you should be nice to your substitute person. It’s not necessary to purr, but you should show your face and maybe rub the substitute person’s pant leg and make some pleasant remark such as, “I know it’s not your fault that my daft person went to Central America, where there are volcanoes and jaguars.” Bizarrely, substitute people often feel more sympathetic to cats who make a great show of coping bravely than to cats who are hiding under heavy pieces of furniture. Ask for extra treats.

Do sabbatical cats get to do anything other cats don’t get to do?

Yes, but on an unpredictable schedule. For example, as a sabbatical cat, I am getting to write this article. Before my sabbatical, I hadn’t written anything in about three years. My person is my amanuensis, and she doesn’t always have time to help me. This is a very common problem among feline authors. My sabbatical person has also had time to buy new file boxes, which are made out of fabric and close with Velcro—much easier to operate (and comfier to nap on!) than the old plastic file boxes were. You can imagine how much I’m enjoying those.

On the other hand, being a sabbatical cat is unlikely to transform your life. I have been enjoying my hallway research project, and my performance art project, and lounging on the file boxes, but in most ways, I’m still the same cat I was before I went on sabbatical.

How can I be a successful sabbatical cat?

I’ve been thinking about this question a lot, between naps and expeditions to the hallway, and I’ve come to the conclusion that the premise is inverted. Successful housecats are pretty much on sabbatical all the time. Snarky people would say this is because housecats have limited responsibilities. Wiser people would note that cats are constantly engaged in thinking, exploring, and being, while remaining blissfully removed from the petty obsessions that occupy so much of their people’s time, such as the never-ending quest to persuade students to put page numbers in their footnotes. In other words, odds are that you are already a successful sabbatical cat before your sabbatical has even begun. The greatest service you can do for your sabbatical person is to try to make him or her behave more like you.