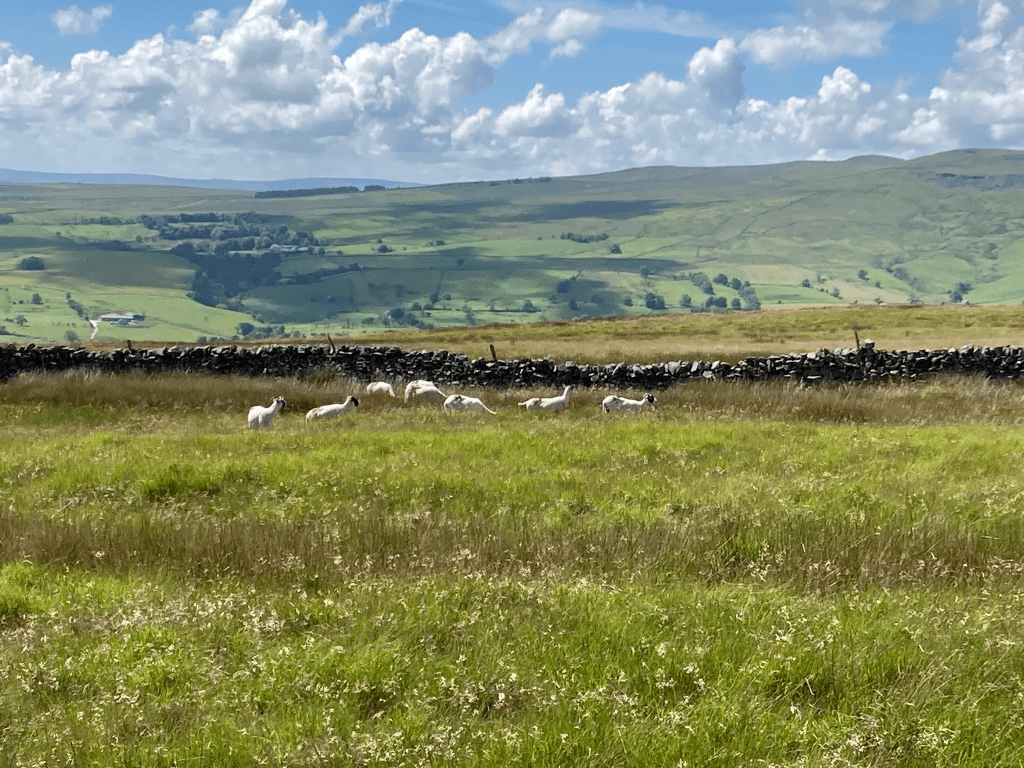

Walking in the English countryside means walking with sheep. Walking in early summer, as I usually do, means threading your way among gamboling lambs and past the tsking ewes who wish their foolish offspring would grow up already, stepping carefully around mounds of fresh and fossilized sheep dip, negotiating flocks of scores and hundreds without a shepherd in sight, and averting one’s gaze from the roast lamb that invariably features on guesthouse menus in the evening.

I got my first taste of walking among sheep a decade ago, at Hadrian’s Wall. I read a lot before I went, including an entire book on Roman Britain; I took advice from the B&B proprietor and equipped myself with Stedman’s guidebook and new boots. But not until I was standing in a field in Cumbria, poised between a star-struck lamb and his annoyed, world-weary mother, did it dawn on me that all the injunctions I had read about respecting livestock did not apply merely to the occasional field crossing and that I would in fact be spending most of the next three days among sheep. This was disconcerting, but exhilarating, too. I grew up in the Midwest; there were farms and cows and sheep everywhere, neatly fenced away. In the landscape of my childhood, one never, ever, got in a pasture with someone else’s sheep.

In the U.K., the popularity of country walking means that peoples of all ages, ranks, and temperaments routinely find themselves in pastures with other people’s sheep. England’s long-distance walking paths feel ancient, but they are actually modern features superimposed on a well-used rural landscape. There were of course medieval paths that led from village to monastery, from hovels to fields to church and manor house, and to the woods when pannage (the freedom to let pigs forage for acorns) and estovers (the privileged of gathering firewood) were rights of common. Beginning in Tudor times, and accelerating over generations until a peak around 1800, most landlords enclosed their farmland by Act of Parliament and converted it to grazing. Villagers lost their rights of common and were sometimes pushed off the land; many then sought work in the booming industrial towns.

Urban living soon made Englishmen and women nostalgic for the land. Nineteenth-century city dwellers turned to country walks for respite from overcrowding and pollution. Factory workers sometimes embraced hobbies such as birdwatching and natural history as an antidote to the dystopian rigors of the workweek, a phenomenon that Manchester novelist Elizabeth Gaskell documented in Mary Barton and North and South. In 1935, enthusiasts founded the Ramblers’ Association to champion public access to country footpaths.

After World War II, the movement to promote country walking became a central component of the U.K.’s national redefinition. The Countryside Code, first developed by the Ramblers’ Association, was officially promulgated by the National Parks Commission in 1951. In 1956, Philip, Duke of Edinburgh, established the Duke of Edinburgh Award for boys aged fifteen to eighteen, with the goal of keeping them disciplined and motivated in the awkward years between school-leaving and National Service. It proved so popular that he soon announced a similar award for girls. Expeditions, typically small-group walking trips in the British countryside, were a central component of the program right from the beginning. In 1965, the U.K. established its first National Trail, the Pennine Way. Today there are more than a dozen, comprising thousands of miles of public footpaths, and many towns and villages maintain local footpaths and rights-of-way.

In the years after my visit to Hadrian’s Wall, I haphazardly acquired more experience of walking among sheep, mainly by doing things wrong. In the Peak District, a guesthouse proprietor sent me over the fields from Bakewell to Edensor to see the handsome Chatsworth Estate. When I approached the gate into the first huge pasture, a pack of sheep mobbed it as if I were a visiting celebrity. Hopping over the stile, I shooed the woolly paparazzi away. I hadn’t gone more than fifty yards before I came to two disconcerting realizations. First, that I was wearing sandals—a singularly unsuitable choice of footwear. Second, that I was—contrary to my intention—herding sheep. A dozen or more had gotten out in front of me and were letting themselves be herded by my quiet progress, disregarding my vocal assurances that I really had no wish to drive them anywhere. They insistently cast me as a shepherd I had no wish to be, while the wiser fallow deer remained coolly at rest under the spreading boughs of trees.

Meanwhile, back in the Midwest, my niece started raising sheep as a 4H project. My exceedingly modest contribution to this endeavor was to teach my younger niece, a toddler, to hand-feed them wildflowers through gaps in the fence. Once, on a solo visit to the barn, I rashly opened the gate to the sheep pen to say hello—and inevitably, the inmates rushed the gate. Soon two sheep were rampaging through the yard. My eight-year-old nephew, the only person within shouting distance, came to my aid. Following our instincts, we each grabbed a sheep: well over 100 pounds of chunky, squirmy, oily, less-than-sparklingly-clean wool. In the midst of this absurd scrimmage, my sister-in-law appeared and told the two of us off for manhandling the sheep. The correct thing to do, she explained, was to “think like a sheep” and manipulate them into wanting to return to the barn. It sounded very sensible, if creatively demanding . . . but I had no idea, and still have no idea, of how to think like a sheep.

A few years later, entranced by the BBC miniseries All Creatures Great and Small, I started to dream of decompressing from the rigors of hybrid pandemic teaching with a walking trip in the Yorkshire Dales. By this point, I knew that walking in the English countryside meant walking among sheep, but I’d gotten used to the idea; it has a certain mucky charm. In All Creatures Great and Small, the menacing figures are generally bulls; horses and dogs are the heroes, and sheep provide comic relief. Sheep are the ones who pass out from terror when tween Jenny’s tween-like dog breaks into their pasture, or respond to a dose of anesthetic meant to ease the passage into the next world by mysteriously perking up and being fine in this one.

Livestock dominate the Dales, which have a population of about two million sheep, half a million cattle, and 24,000 human beings. Ninety-five percent of the land remains in private hands, and even the public lands succor cattle and sheep. (The National Trust rents grazing rights to local farmers.) Helpful signs warn walkers not to annoy the livestock, explaining graphically that two meters equals the length of one bull or two Swaledale ewes. Cattle pose the greater challenge to walkers. They are large and edgy; each herd seemed to have a head cow, or a pair of rival head cows, who fixed me in their gaze and maintained silent, resentful eye contact from the moment I arrived until I clambered over the next stile. Coming down from Malham Tarn, I encountered a pair who positioned themselves in front of a signpost I desperately needed to read. Helpless, I guessed at my general direction and struck a path, hoping for the best. Years earlier, on a stretch of Hadrian’s Wall near Sycamore Gap, a lone brown cow had lumbered onto the path and blocked it, for no clear reason except that she did not want me to get to Housesteads. Sometimes it feels like the cows are deliberately nettling the tourists.

Sheep are an altogether easier proposition. They’re not very bright, and I often find myself flummoxed by how they respond to me. More than once, in my forays through pastures in the High Dales, eight or ten sheep got out in front of me and—just like those sheep on the Chatsworth Estate— hurried along the narrow path as if I were herding them. Perhaps they fantasized that I would release them into another pasture, a longed-for expanse of taller grass and fewer stones.

But even sheep enjoy the occasional exercise in humiliating tourists. My final day in Malham dawned with a new moon and a night of violent rain. I had planned a rather tame outing over the fields to Kirkby Malham and Airton, tea at the local farm shop, and a pretty stroll along a stretch of the Pennine Way that hugs the banks of the River Aire. On the map, this looked straightforward, flat, and easy. But I couldn’t locate the footpath to Kirkby Malham and, with my sneakers sodden from looking, struck out along the road instead, dodging delivery vans on blind corners. After a brief stop at St. Michael’s of Just-Missed-the-Domesday-Book, I sought and found a signpost for Airton. The arrow indicated a narrow, muddy trail, hedged with stinging nettles, three-quarters of the way up a steep river bank. Struggling to keep my balance when my left foot was never on the same level as my right one, I very nearly ended up at the bottom of the bank, lacerated by nettles. Still, I persevered and at last stumbled on a gate leading into a vast expanse of pasture—and, off to the right, a very nice set of stone steps leading down to the church parking lot. (This was not the only time I got the impression that the people of Yorkshire didn’t want visitors to know too much about local shortcuts.)

Clutching my £2 map from the National Park Centre, I gamely tried to navigate two miles of pastureland by landmarks such as a triangular copse of trees. It was not a success. I underestimated the distances on the map, which, given its inexplicable omission of the stone steps, I no longer trusted much anyway. Eventually I was rescued by a farmer, who advised me that I was so far away from where I was supposed to be that I had better let myself out via his driveway and follow the main road to Airton. His sheep, lounging in the damp grass, rolled their eyes. I got a cherry scone at the farm shop (I needed it), located the Pennine Way, and struck out for Malham.

Slipping and sliding through mud to Hanlith, I crossed an enormous pasture that hosted both cattle and sheep. The cows eyed me menacingly; the sheep seemed more inclined to show off. An audacious lamb bounded across the footpath, a hundred yards from its mother, then erupted in panicked bleating. Was it my imagination that the mother replied in scolding tones? Meanwhile, another ewe arrayed five lambs around her and urgently sought eye contact with me. I may not know much about sheep, but even I know that laying claim to quintuplets is a ridiculous brag. Still, on her turf, I could only nod and say, “Yes, dear, very well done.”

At Hanlith I crossed the road, labored up the hill, dodged a postal van careening down, and looked about for one of the reliable signposts that dot the English countryside. I saw one, but it consisted only of a post sticking up at random from the grassy verge—the signs had evidently been removed. Still, I knew from the map that the next segment of the Pennine Way lay part-way up this hill, and I knew I was at the edge of Malhamdale; I could almost see my hotel in the distance. I plunged ahead.

The pasture was not a hospitable one. It was large and long and steeply pitched, with the sheep congregating at the bottom of the hillside. After a couple minutes I wasn’t sure whether I could make out the footpath or not. I clung to the high ground until its unevenness began to make me fear for my ankles. I picked my way down the stony, boggy hillside and made for the far gate, thinking longingly of my hotel room and the satin ballerina slippers waiting for me there.

At this point the sheep perked up, noticed me for the first time, and militantly protested my presence. An indignant ewe rounded up her twins and rushed me with surprising speed as I dashed for the gate. Scuttling through it, I paused to loop the rope over the post and saw that all three, mother and offspring, had turned to moon me and were pointedly urinating on the ground where I had stood a moment before.

Later I learned from the occupant of a nearby holiday cottage that I had, in fact, missed the Pennine Way. It was one pasture higher up than I had guessed. The sheep, of course, had known this. They knew the geography of who got to go where; they knew the rules better than I did.

Though walking among sheep can be frustrating—and messy—something keeps pulling me back. Even as I type these words, I am mentally planning another jaunt to the English countryside, which will surely include days of walking among sheep. Whence the allure? English country walks offer an intriguing blend of comfort and getting away from it all. It’s nice to stand on a hilltop in England’s big sky country at three o’clock, glorying in majestic solitude, and sit down to a cream tea at four.

But that’s not quite the answer, because a walker who finds herself sky-gazing at Weets Top, a summit overlooking Malham, is not really in the middle of nowhere; she is a wayfarer through a well-tended landscape that, over many centuries of human, bovine, and ovine habitation, has achieved some sort of sustainable balance of uses and activities. Sharing space with the locals is just as much part of the charm of English country walking as it as of staying in an Airbnb. You feel the land has meaning beyond your temporary presence on it. The Dales have been farmed and grazed for thousands of years; the Norse terracing that can still be glimpsed at Malham Cove bears witness to this. The sheep I encountered are guardians of a centuries-old way of life, brilliantly evoked by James Rebanks of the nearby Lake District in A Shepherd’s Life: Modern Dispatches from an Ancient Landscape (2015). Walking England’s rural footpaths puts wayfarers in touch with the rural economy and the bones of local history, but also with the lesson that the landscape we traverse is ever and always a shared one.